Fishing for Snow, and the Heart of the Lake

A problem and a translation, eight centuries apart

I was going to illustrate the piece below with an unrelated painting, but captioning the painting meant translating the title, which meant choosing an interpretation of the poem it alludes to, which meant adding my own unsatisfying translation to a growing pile of unsatisfying translations. You know how these things go.

The title comes from a poem by Liu Zongyuan 柳宗元 (773 - 819). I don’t think I’ve seen a translation I liked yet, and this is not about to be the first, but as quickly as I can:

Liu Zongyuan 柳宗元 - “River Snow” 江雪

千山鳥飛絕 萬徑人蹤滅

孤舟簑笠翁 獨釣寒江雪

a thousand hills and not one bird in flight

a million trails and not so much as a footprint

lone boat, rush cloak, reed hat: an old man

fishes alone in the freezing river for snowThis is a B- first draft and I’m about to poke a bunch of holes in it before setting it on the shelf to mature. For second through dozenth opinions, see Victor Mair’s Language Log post, which reproduces an older short essay by Lucas Klein about readings and renderings of the poem. (The comments are also good — I recommend Diana Shuheng Zhang’s in particular.) I’m less crazy about this draft now than I was at the beginning of this paragraph, and not at all sure about that spacing, and the first two lines are wrong or at least missing the point. Let’s reread:

1:

千山 a bunch of hills

鳥飛 bird(s) fly/flight

絕 is ceased2:

萬徑 a bigger(?) bunch of human-made paths

人蹤 human tracks

滅 are eliminated

My first draft falls into the same thing as a lot of the other translations: I mistook 絕 and 滅 as just a dramatic way of saying “there aren’t any birds, and footprints are another thing there aren’t any of.” But there are a couple things going on here, I think. One is the sound dimension: 絕 and 滅 were checked-tone 入聲 words, meaning that for Liu Zongyuan they ended abruptly in stop consonants (dzjwet, mjiet).1 The words also have a sense of being brought up short: 絕 can be “to cut off” or “to be cut off,” but the passive construction in English implies the existence of an agent that the Chinese stative verb doesn’t. Same problem for “is obliterated.”

If I come back for a second draft, I think the thing to focus on will be the sense of things normally present — birds in flight in the natural world, footprints on the paths in the human-made world — being completely absent, which I take to be the operative sense of 絕 and 滅 here. If you can avoid assuming an agent: Amid hills, the flight of birds is ceased; on multiple trails, signs of people passing that way are erased.

3:

孤舟 solitary boat,

簑 straw rain-cloak,

笠 straw/bamboo hat

翁 old man

4:

獨釣 alone fishing(-for?)

寒 chill(,?)

江 river(,?)

雪 snow

I think the main question in the third line is whether to read three and four as verbal montages (flashing from the lone boat to the straw cloak to the bamboo hat to the old man) or as single images: in a solitary boat, an old man in a straw rain-cloak and bamboo hat. Because of the requirement for parallelism, your preferred reading for line three will influence (though not necessarily determine) your reading of line four, which is the interesting one.

Most translations go with the majority reading, “fishing alone on the cold river amid the snow.” This is definitely not wrong! That image and that line are absolutely in the Chinese. But I think “fishing for snow” is in there too, and that ending on an image of futility, rather than just cold, fits better with the first two lines as I understand them, and with the context Liu Zongyuan wrote them in, which was exile.2 So reread again, start to finish, unrolling the poem like a painting of a landscape. With rhyming lines marked:

Hills — birds flying? ceased. (dzjwet)

Paths — human footprints? obliterated. (mjiet)

Lone boat — rush cloak, reed hat — old man.

Solo angling — freezing river — snow. (sjwet)

The first two lines present an image, then immediately identify something missing, at smaller and smaller scales. I think the last line does the same thing, with 釣 “angling (for)” baiting the hook: we’ve made it all the way down to the bottom of our landscape scroll with this poor old insufficiently weatherproofed guy in the freezing river with his fishing rod — and there’s nothing to be caught but the abrupt stop-consonant of sjwet, “snow.”

Like deciding whether 山 is “mountain” or “hill,” this is an English problem, not a Chinese one: “fishing amid” and “fishing for” are both latent in the original, and it’s only our own barbarous language that has to choose. I may end up choosing differently if I come back for a second draft in the new year — I was reading under the influence of having recently been outside shoveling snow — but I went down this rabbit hole because I was just trying to justify the translation of the title of an illustration for the thing I’m about to finally get to, which has nothing to do with the painting except insofar as both have snow in them. You see what it’s like, doing this stuff.

Now for the fun part!

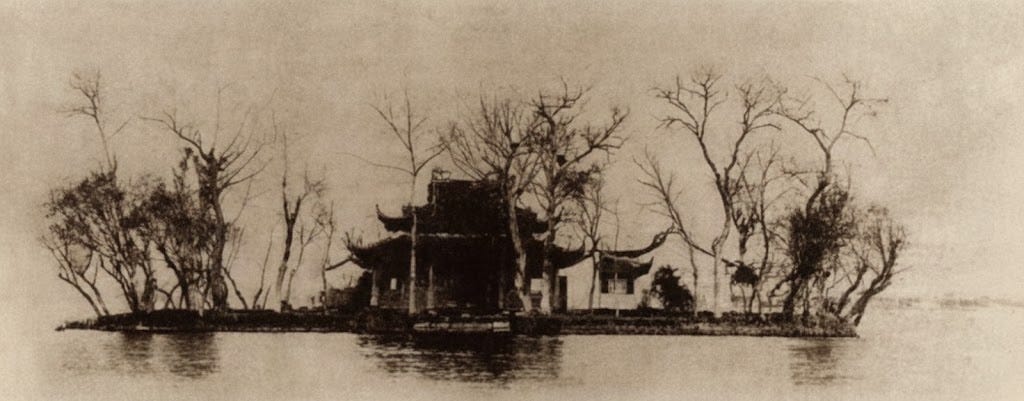

Before I fell down the rabbit hole of that caption, I was looking for a painting to illustrate “Watching the Snow at the Heart-of-the-Lake Pavilion” 湖心亭看雪, a vignette from Dream-Memories 陶庵夢憶 by Zhang Dai 張岱 (1597-1684), whom I’ve mentioned before.

Zhang was born into a well-connected gentry family from Zhejiang in 1597, at the tail end of the Wanli emperor’s reign. He spent his first four and a half decades (and his family’s money) as a serial enthusiast and connoisseur of most things that could be appreciated, not excluding the pleasure quarters around the West Lake 西湖 in Hangzhou 杭州, where this vignette is set. Dream-Memories is Zhang’s reminiscences of those times, recalled and reconsidered from abject poverty on the far side of the Ming collapse.

Zhang famously disdained anyone without a fixation or two — 人無癖不可與交,以其無深情也 — on the grounds that such people were incapable of deep feeling. Whatever the boatman at the end of this story might’ve been thinking, “mad,” in the sense of “being mad for something,” was a compliment as far as Zhang was concerned.

Watching the Snow at the Heart-of-the-Lake Pavilion

When I was staying by the West Lake at the end of the Chongzhen Emperor’s fifth year (1633) there were three days of heavy snowfall, and the usual sounds of humans and birds on the lake were replaced with silence. One evening I took a small boat out to Heart-of-the-Lake Pavilion, wrapped tightly in furs and huddling over a charcoal brazier, to watch the snow just as night was falling. Sky, clouds, hills and water were all an unbroken white in the fog and frost, and the only reflections in the lake were a slash of causeway, a dot of pavilion, a mustard seed of a boat and the two or three specks of ourselves aboard it.

We arrived at the pavilion and found two people sitting on a felt blanket, with a serving-boy warming wine in water that had just come to a boil. They were pleasantly surprised to see me – “Who’d have thought there’d be someone else out here!” – and dragged me over to drink with them. I forced down three mugfuls at their insistence and excused myself, though not before asking their names. Visitors from the southern capital.

“The gentleman may be mad,” the boatman muttered as I got back into the boat. “But it looks like he isn’t the only one.”

I think this was less rare for Tang poets than later ones? Not checking! This caption has gone on too long already.

I’ve bracketed “-for” in my gloss of 釣 because my zero-research, not-even-my-millennium, this-is-moot-because-the-rules-of-tonal-scansion-rule-out-anything-else-anyway impression is that verbal 釣 is more apt to want an object, which is why it shows up in lines like 只釣鱸魚不釣名, “He only angles for lake perch — he doesn’t angle for fame.” In retrospect this is probably a big part of why I read the line as I do. (As is the title of the painting.) Don’t quote me on this! I may have got it completely around my neck and I’m not even going to attempt to check it until I come back for a second draft.

I'm starting to feel a bit of bolshy rage with these landlords who go out into nature in pursuit of solitude - only with two or three porters and boatmen in tow, who apparently don't count as human beings.

My feeling for 钓 is that it does like to have something after it, but it doesn't have to be a direct object. A locative works equally well, so there's a lot of 钓台ing and 钓江头ing, for example. The combinations 钓雪 or 钓冰 don't appear in the 全唐诗.

I certainly think that the 蓑笠翁 is intensely visual, and is describing some sort of shift in focus. I think of it as a zoom in, which is obviously very anachronistic, but given the kinds of paintings that we believe they were making at the time, I wonder if the wording is reproducing brushstrokes. One stroke for the boat, one for the cape, one for the hat, and there's your man (no more strokes required).

絕: extinct 滅:extinquished, maybe? And, to a Chinese, “fishing amid snow” is definitely more probable than “fishing for snow”, orders of magnitude more probable. 😊