Tao Yuanming - “Home Again”

Monday Motivation from medieval China's best-loved proponent of loud-quitting

結廬在人境,而無車馬喧。

問君何能爾,心遠地自偏。

採菊東籬下,悠然見南山。

山氣日夕佳,飛鳥相與還。

此中有真意,欲辨已忘言。I built my cottage in the realm of men,

and yet there's no clamor of carriages or horses.

How, you ask, can it be so?

When the mind is detached, one's place becomes remote.

I pick chrysanthemums by the eastern hedge,

catch sight of the southern mountain in the distance.

The mist on the mountain is radiant in twilight;

birds on the wing make their way home together.

In all this there's some truer meaning —

I'd tell you, only I've forgot the words.(Tao Yuanming 陶淵明, “Drinking, V” 飲酒,其五)

Sooner or later, as you scan through Charles O. Hucker’s A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China, you’ll come across a job title — for me it was Dough Pantry Supervisor — that makes you wonder what Mondays felt like for history dudes.1 Did the Rectifier of Governance go to work with a spring in his step? Did people around the office grumble about the Marquis for Venerating the Sage being a nepo baby?

I like to imagine that some nontrivial percentage of officialdom started its week by wistfully muttering Tao Yuanming’s poem “Home Again” (歸去來兮辭) to itself. Tao, the greatest poet of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, was born to a minor southern gentry family under the Eastern Jin and died a few years into the Liu Song. It was not a great time to embark upon a public career — it had not been a great couple of centuries — and after unhappily occupying and resigning a string of minor official posts, the last of which he reportedly held for less than three months, Tao finally renounced public life altogether and retired to his farm, where he proceeded to invent a poetry of individuality and authenticity. It started, supposedly, with “Home Again,” which he is said to have written after abruptly quitting his post as magistrate of Pengze:

Off home again!

My fields and garden will be choked with weeds. What's keeping me?

It was me who made my heart my body's thrall —

why go on being disappointed, lonely, and sad?

I realize: the past is beyond repairing,

but what's ahead is still worth pursuing.

I went down the wrong path, yes — but not too far.

I can tell that this is right and that was wrong.A light breeze rocks my little boat,

my robes flutter in the wind.

I ask a fellow traveller the way,

begrudging dawn its dimness.At the sight of my cottage

I break into a joyful run.

The servant boy welcomes me,

and my young sons await me at the gate.

The three pathways are nearly overgrown,

but the pines and chrysanthemums are still there.

I take my sons' hands and go inside,

where a full jar of wine awaits.

Drawing the wine to me, I fill a cup,

And a glance at the trees brings a smile to my face.

I lean out the south window and look down on the world —

This tiny space will be roomy enough for me.

Daily walks in the garden are my pleasure;

There's a gate, but we mostly keep it shut.

I lean on my cane, strolling or resting as the fancy takes me,

Or sometimes looking up off into the distance.

Clouds, having nowhere to go, appear from behind the mountain;

Birds, tired from flying, know their way back home.

The light dims as the day draws to an end,

and I circle a solitary pine, running my hand over the bark.Back home again!

Let the ties that bound me break, and my wanderings end.

The world and I are done with one another.

Why would I ever harness my carriage again?

I'll take pleasure in honest talk with friends and family,

Enjoy my zither and books to banish cares.

The farmers told me spring is coming,

and there'll be work to do in the west fields.

Sometimes I'll call for a covered carriage

or row a solitary boat,

Wind my way through narrow gullies

or cross the hills on rough and rugged paths.

Trees burst into luxuriant bloom,

and springs babble back to life again.

Admiring the way all things know their season,

I am moved at the thought that my life will run its course.And then no more!

How little time we have in living form —

Why shouldn't we follow what the heart dictates?

What’s all our fussing and fretting for?

Rank and riches aren't what I'm after,

and I hold out no hope of Paradise,

But to go out on my own on some fine morning,

planting my staff in the ground as I take up a hoe,

or climb the east hill, whistling slow,

or compose poetry beside the limpid stream —

So I’ll take what comes until my last homecoming,

delighting in what Heaven has appointed. What else could I need to know?

Happy Monday!

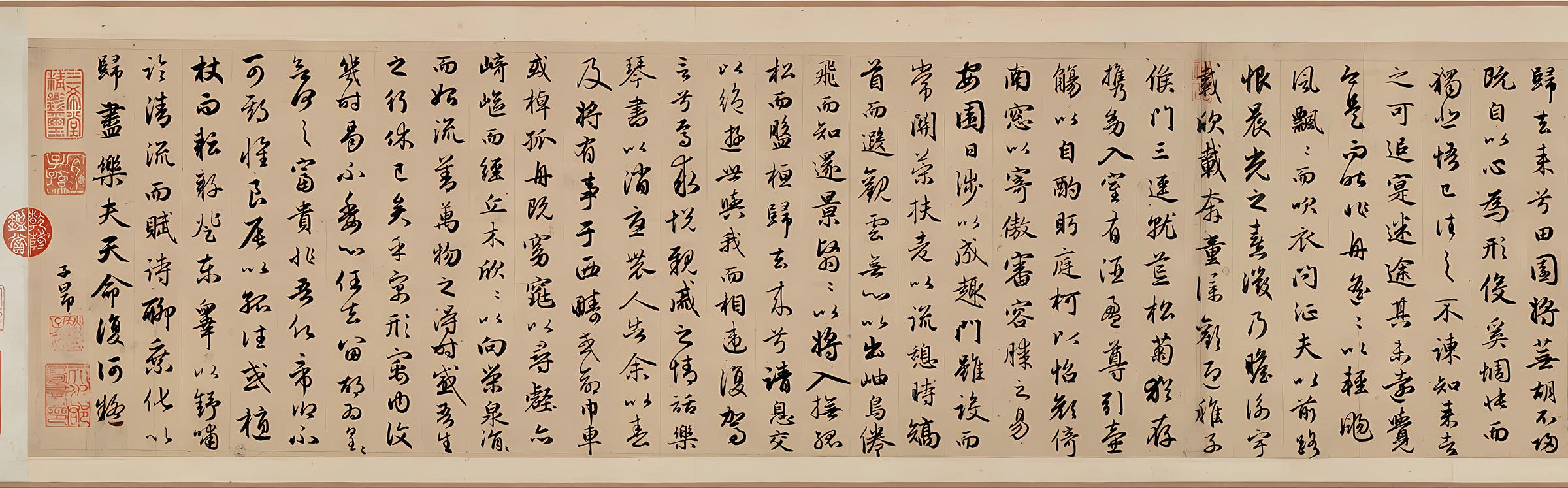

When people encounter this poem — and pretty much everybody literate in Chinese has — it’s always with the preface, which I left off here (and sacrilegiously cropped out of the Zhao Mengfu calligraphy above) for a couple of reasons. The first reason, and the main one, is that I want you to like Tao Yuanming, or at least not be actively irritated by him. My translation of “Home Again” may or may not work, but with any luck it will not have made you think less of Tao as a person2 — whereas when you translate the preface out of the literary and cultural context that it’s acquired over the past millennium and a half, Tao ends up sounding like a very recognizable Type of Guy:

I was poor, and what I got from farming was insufficient to provide for my family. The house was full of children, the grain jar was empty, and I could see no way of supplying the necessities of life. More than once, friends and family urged me to take an official position, but when I took their advice to heart there proved to be no way forward. As it happened, I had some business abroad, and gave the grandees the impression that I was a thoughtful, painstaking person. An uncle, seeing the dire straits I was in, arranged a small-town posting for me, but the land was still in turmoil at the time and the thought of such a remote posting frightened me.3 Pengze was only 30 miles from my home, and a posting there came with public fields whose harvest would suffice to keep me in wine,4 so I sought a posting there. It was only a few days before I was seized with the urge to go back home again.

It is in my nature to be what I am, and no amount of discipline or restraint will change that. Miserable as it was to be cold and hungry, it was the going against myself that truly sickened me. Every time I attempted to do the bidding of others I was acting as bondsman to my belly, and realizing this filled me with shame and regret at having so betrayed my principles. I resolved to hold out until the next harvest before packing up my clothes and slipping away under cover of night — but then my sister who had married into the Cheng family died in Wuchang, and I could think of nothing but getting out as quickly as I could. I left the position of my own accord. I was an official for just over eighty days, from mid-autumn to winter, before circumstances made it possible for me to do as I had wished. I call this piece “Home Again.”

11th month, yi-si (405 CE).

The other reason is that it’s not at all clear how much of the preface is Tao’s.

Think back to our seventh-century Dough Pantry Supervisor for a minute. If he has a copy of this poem, it’s a handwritten one, copied from another handwritten copy of a handwritten copy. Centuries of brush and paper separate Tao Yuanming from the first printed edition of his works.

People knew this was a problem. Take another look at the shorter poem, “Drinking, V,” that I opened with: The Song-dynasty poet Su Shi 蘇軾 deplored the widely circulating version that had 望 wàng, “to gaze at,” instead of 見 jiàn, “to catch sight of,” in line 6, on the basis that the Tao Yuanming he knew would never spoil the effect of spontaneity and detachment by doing anything so gauche as gazing, and concluded that “gaze” must be an error by copyists who didn’t actually get what Tao was about at all. Su’s friend and protégé Chao Buzhi 晁補之 quotes Su’s reasoning:

"‘[I pick chrysanthemums by the eastern hedge, / and gaze at the southern mountain in the distance]’ —picking chrysanthemum flowers and gazing at the mountain at the same time would have left no room for further thought, which is not the original intention of Yuanming. If the couplet goes ‘[I pick chrysanthemums by the eastern hedge, / and catch sight of the southern mountain in the distance.],’ then it shows that the poet was just picking chrysanthemum flowers and did not mean to look at the mountain; only accidentally did he raise his head and see them, and thereupon in a detached manner he forgot about his feelings, his mood one of relaxation, and his mind remote.”5

Su’s preferred reading became the standard version of the line, and although it is an extremely bad idea to disagree with Su Shi in matters of poetic taste, the earliest surviving copies of the Wen xuan 文選 — the anthology “Drinking, V” is collected in — all have “gaze at” in line 6, and the Tang poet Bai Juyi 白居易 wrote a poem in imitation of Tao Yuanming containing the line “I sit and gaze at the southeastern mountain.”

I’m going somewhere with this, I promise.

The Wen xuan also contains “Home Again,” but the preface is a lot shorter and has none of the flaky pisshead self-aggrandizement of the received version. All it says is:

I was poor, and the thought of taking a remote posting frightened me, but Pengze County was only 30 miles from my home, so I applied for that. It was only a few days before I was seized with the urge to go back again, so I left the position of my own accord. Circumstances made it possible for me to do as I wished. I call this piece “Home Again.”

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the longer preface is a fake, but it does invite us to take a closer look at it. The dynastic histories of the Liu Song and the Jin both contain the text of “Home Again,” but omit the preface. Tao’s biography in the Jin history has him leaving office in 406, not 405 as the received preface has it. And if we’re being skeptical here, that line about Tao only taking the job so that he could brew beer with grain from public fields starts sounding suspiciously familiar from anecdotes about other eccentric figures: According to the New Account of Tales of the World 世說新語, the 3rd c. oddball Ruan Ji 阮籍 once asked to become an infantry commander because he’d heard they kept a lot of booze in the commissary. The dynastic histories do report that as magistrate, Tao ordered that the public fields be planted with glutinous (i.e., fermentable) grain — but then again, the received preface has Tao in office from the eighth to the eleventh months, putting him in Pengze at precisely the wrong time for planting. And while we’re at it, Tao’s biographies all have him loud-quitting his job in far more spectacular fashion than the preface does:

The commandery sent an inspector to the county, and Tao's subordinates told him he should tie on his girdle and call on the inspector. Tao sighed: "I cannot bend at the waist before some country ignoramus just for the sake of my five pecks of rice." That very day he untied his seal ribbon and quit his job.6

This is the most famous episode from Tao’s life story — “not bending at the waist for the sake of five pecks of rice” (不為五斗米折腰) became a conventional way of saying someone was 2 legit 2 start — but it’s not supported by anything claiming to be Tao’s own account of how he quit his job. It’s certainly the sort of thing one can imagine Tao Yuanming doing — but one imagines Tao Yuanming on the basis of Tao Yuanming’s poems, and Tao Yuanming’s poems turn out to have been modified in places, and possibly expanded, to bring them more into line with…the way people imagined Tao Yuanming.

It’s a tidy little feedback loop: poems shaped by images formed by the same poems. If the received preface makes Tao look like a certain Type of Guy, perhaps it’s because people read Tao’s works assuming him to be that Type of Guy, “corrected” the works when they didn’t fit with what one would expect from that Type of Guy, derived biographies from motivated readings of modified texts, and reread and retransmitted Tao’s works with that Type of Guy in mind. Lather, rinse, repeat.

So congratulations and/or condolences to Tao Yuanming, who rejected conventionality so beautifully that he became a new convention, a type-specimen of the literary individualist, authentic to other people’s ideas of who he was. There’s no escape: Quit your job, shun the common crowd, move to the countryside and get as drunk as you want — the Man will still get you in the end.

Happy Monday!

麴麪倉督 qūmiàn cāng dù — SUI-TANG: Dough Pantry Supervisor

2 subordinates in the Office of Grain Supplies (daoguan shu) of the Court of the Imperial Granaries (sinong si); responsible for providing the palace with yeast, flour, and dough; discontinued in the period 627-649.

I also have to mention Hucker’s translation of 神威軍 shénwèi jūn as “TANG: Army of Inspired Awesomeness,” in case anybody is looking for a band name.

You may want to look at James R. Hightower’s “The Return: A Rhapsody” for a second opinion — the translation starts on page 213. I owe him for a few turns of phrase in my translation of the preface, particularly “grandees” for 諸侯.

This part isn’t just Tao Yuanming being precious: the “turmoil” (風波) is presumably a reference to the military campaigns that began after Huan Xuan 桓玄 (369–404), the son of a Jin general, declared his own dinky little fail-dynasty in 403, and continued even after Huan’s beheading half a year later.

I’m doing the conventional thing of translating 酒 as “wine” even in contexts where it was almost certainly “beer.” That said, I would love to see someone who is not me translate, e.g., the Tang poet Li Bai’s 月下獨酌 as “Cracking Open a Cold One with the Moon.”

Modified slightly from Xiaofei Tian’s Tao Yuanming and Manuscript Culture, p. 34, which is my source for this and is extremely worth reading for anyone interested.

In "The Banished Immortal" Ha Jin recounts the scene where Li Bai visits Tao's cottage some 300 years later.

"About eight miles north of Mount Lu was a hamlet called Shang-jing. The poet Tao Yuanming (376–427) had once lived there. It was remarkable that Li Bai journeyed to the small village to look at Tao’s homestead and pay his respects at his grave, which had fallen into disrepair, the words on the stone hardly legible. Like his deserted homestead, Tao had remained obscure for more than three centuries after his death. Only two decades prior to Li Bai’s visit had Tao’s poetry begun to be recognized by Tang poets, particularly for his presentation of immediate experiences in nature and the daily life of the countryside. Evidently Li Bai was one of his new admirers. Viewed from Tao’s homestead, Mount Lu loomed in the distance, often half-hidden in clouds, against which birds sailed in the misty sky. The sublime scene depicted in Tao’s poem “Drinking Wine” must refer to this view: “Picking chrysanthemums under my eastern hedge, / I raise my eyes and see the mountain in the south.”"

Ha Jin's translation here adopts "see" rather than "gaze". Although the scene he describes of the mountain in the clouds with birds brings to mind Du Fu's 望岳 where "gazing" is definitely the order of the day.

This problem of historical layers of shading is really interesting. One of the most interesting bits of writing that I can never find again was about the manuscripts of Li Bai, with a hint that one of his most "characteristic" lines may have been a later interpolation based on the myth of Li Bai that was already developing by the end of the Tang.

I chase my tail for days sometimes wondering how much it matters, given how poetry/writing in general is so much a form of self-mythologising anyway...

But yes, it's a nice translation, and it's certainly often true that these old writers absent their centuries of curation come across as weirder and more engaging.